Alberta Review: The Game

Hockey writing could be so much more, as Dryden showed

The best and fastest way for this to grow is for you to share the posts within your networks. A forward goes a long way, and the more subscribers we get, the more I’ll be able to write. The writing may change in the next few months to be a bit more entertaining (we hope) so tell your friends!

Most hockey writing – most sports writing, for that matter – has forgotten the romance, joy, and narrative that once dominated the craft. It is clinical, focusing on analytics, critical, focusing on management or coaching, mistakes, or gossip, striving to be the first piece to leak a new deal or locker room headache. I was thinking about this as I read the tributes to Ken Dryden, who was more than a great hockey player; he was a great hockey writer, possibly the greatest.

Dryden’s book The Game is the best book about hockey, but it was a 2021 article in The Atlantic, “Hockey has a Gigantic-Goalie Problem,” that first alerted me to his writing, and showed how it remained possible to write intellectually and emotionally, not analytically, about sports.

Once they had the equipment and the strategy, goalies focused on putting all of this into play. Particularly intriguing is to watch them position their body when the action is to one side of their net, near the goal line. On their knees, one leg extended to the bottom far corner, the top of that leg pad filling the five-hole, their upper body crammed up against the post, their shoulders shrugged upward to take away the top corners, all of their body parts coming together so seamlessly. It is like watching an origami master in action, constructing not a paper crane, but a perfect wall.

…

So for shooters and coaches, that is the strategy. Rush the net with multiple offensive players, multiple defensive players will go with them, multiple arms, legs, and bodies will jostle in front of the goalie, and the remaining shooters, distant from the net, will fire away hoping to thread the needle, hoping the goalie doesn’t see the needle being threaded, because if he does, he’ll stop it. The situation for the shooter is much like that of a golfer whose ball has landed deep in the woods. He’s been told many times that a tree is more air than leaves and branches, but with several layers of trees in front of him, somehow his ball will hit a leaf or branch before it gets to the green. Somehow, the shooter’s shot will not make it to the net. So he will try again. Because what else can he do?

The result: This game, one that allows for such speed and grace, one that has so much open ice, is now utterly congested.

His argument that goalie equipment was hurting the game was argued with rose-coloured glasses fully secured on nose. Remember, nostalgia is not always a bad thing, especially in a day and age that feels increasingly worse, largely because we’ve ignored the rosy lessons of the past. But he was also making a bigger point—using basketball as an example—of how small and seemingly subtle rule changes can fundamentally alter the nature of a sport. It is writing not just about a singular game, but seeing the threads that link it to a bigger idea. That’s great writing, no matter the topic. In hockey, in the years since Dryden wrote this piece, players have adapted. Even defencemen are able to hit the tightest corners now.

(Of course, Draisaitl, a skilled forward, does it better)

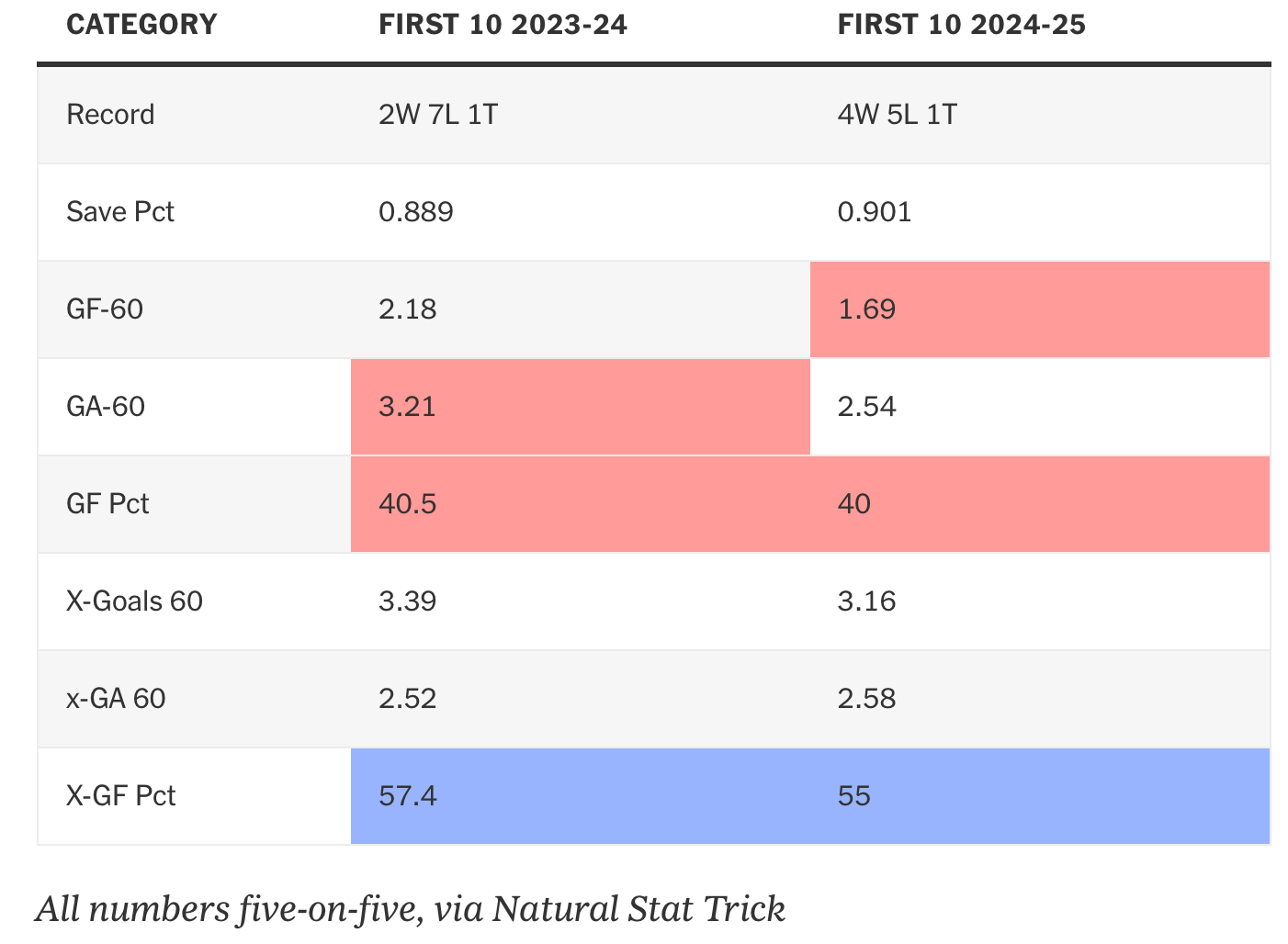

Sports is a business, of course, and analytics dominating the written discussion feels like a continuation of that business mindset dominance. Take a look at this article in The Athletic about the Oilers’ recent history of slow starts. It’s full of charts like this:

(Mitchell’s work is great and I don’t mean to demean analytics or its writing—just that it is getting too prevalent and dominating)

I’m sure the rapid rise in sports betting via smartphone has contributed to the popularity of analytics as a discussion as much as Moneyball did. I recently read a book called The Eye Test: A Case for Human Creativity in the Age of Analytics by Chris Jones, where he argues for more humanity in decision-making as analytics takes over. On baseball analytics specifically, he notes that, analytically, Derek Jeter is a bad player using Ultimate Zone Rating (UZR), where a value is given in runs, either saved by a good defensive player or given up by a bad one. According to UZR, in 2010, when Jeter committed only six errors and won a Golden Glove, Jeter was the third-worst among American League shortstops. The guy who did this:

Fittingly, Jones quotes Paul Maurice (who coached the Florida Panthers (spits) two straight Stanley Cups), who says, of analytics, “God, they do a horseshit job of telling you what five guys do.” Hockey is a team sport, and chemistry cannot be modelled or predicted.

As The Eye Tests attests, the romantic notion brought by literary writing about sports should never—and can never—be lost if we are to fully understand the human reality of a human-dominated realm like athletics.

This is especially true when it comes to hockey, which is such a core part of the Canadian identity (identity, of course, being one of the most romantic and subjective concepts we have). The essential nature of hockey—violence when necessary but not necessarily violence—encapsulates perfectly who we are as a country. The post-playoff series handshake line, replete with sweat, hugs, and tears, is something unique to sport, and likely wouldn’t exist without the Canadian spirit underpinning it. Hockey’s essential nature is something to strive for, just like Canadian identity is something to strive for. Even for those of us who weren’t privileged to play the game, it is easy to see the need for hockey’s dominance of Canadian culture for Canada’s sense of self and independence, as much as Canada needs to dominate hockey to have a prominent brand on the world stage. Hockey, The Hip, and hard work. That’s Canada.

To many Albertans, a big chunk of Canada has forgotten about that identity. Many see this as new, but there has always been a “snobby” Canada that wanted to be seen as far more than hewers of wood and drawers of water (industries that encourage and build the strength and skill necessary for hockey, by the way). We just hear about it more in the social media age than we did before. That element is a part of Canada, and always will be, but the silent majority still wants to have some beer and watch a game. All Canadians, and especially those frustrated Albertans, would do well to remember that.

Canada right now is in one of its historical fits of needing to define ourselves in opposition to our southern neighbours, as the Four Nations Face Off showed, hockey is, more than anything else, how we do it:

Hockey in Canada is inherently political, and it is a core part of our identity, forming it and embodying it. Our writing should reflect that too (as Senator David Adams Richards once pleaded). There are works out there that reflect it in popular writing, like Hockey Dreams and The Country and the Game. Unfortunately, people read few books, but a lot of online articles. Maybe the latter needs to match the former in romantic descriptions of the game, and the irony is, our commentators are verbose and descriptive (Jack Michaels) or sentimental and historic (Ron Maclean). Our written stuff on hockey just needs to keep pace to bring that to even more people.

Alberta Review relies on subscriptions to operate (we hate ads, and they’re kind of pointless). Please consider subscribing to support the publication.

Alberta Review is in no way associated with previous iterations of the publication Alberta Review.