Alberta Review: Generational Views

Many generations see their times as dark

I greatly appreciate your continued support. Alberta Review has some aggressive growth goals this year, but we can’t do it without your support. We live in exciting times, and my goal is to inject some semblance of perspective.

If you think that could help us all, please forward this email or share it on social media. Also, liking this post helps our visibility in the Substack network (but sharing and forwarding are the best).

Thanks again for your time.

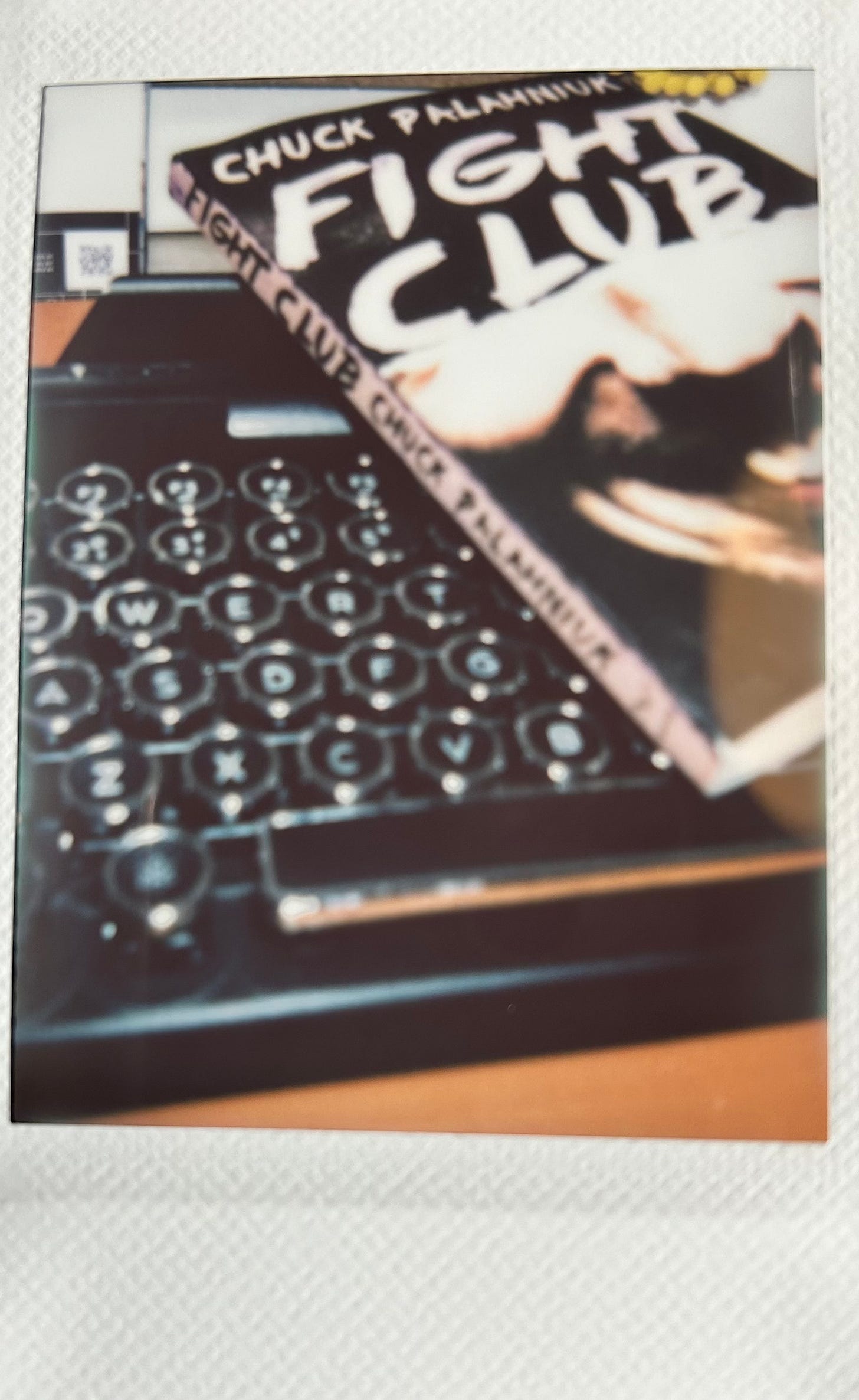

Fight Club is frequently cited as the quintessential novel (and, I suppose, movie) of Gen Xers (roughly speaking, those born between 1965 and 1980). There’s a lot more to the book than the eponymous fight clubs and subsequent violence, of course, but at its core, it’s about the feeling of meaninglessness that a post-Cold War world had produced. The search for meaning leads the characters to nihilistic depravity and violence, and it is a truly dark novel, both the overarching storyline of descent and the narrator's internal justification and lack of empathy. This is a generation that felt invisible then (and feels the same now), as the narrator, “Joe,” sums up when talking about his search for meaning—and sleep—by crashing support groups:

“This is why I loved the support groups so much, if people thought you were dying, they gave you their full attention.”

What’s notable reading it now (as I did over the Christmas break) is that Millennials, a cohort of which I am a part, would look back on the 90s and see a utopia: high-paying jobs, affordable homes, and the guarantee of upward financial mobility. The exact opposite of how Fight Club painted it: “We are the middle children of history.”

Now, looking back, we see the decline in the sense of belonging as globalism took root, but at least personally, you could succeed. Now, much of that seems in doubt. In 2022, StatsCan noted that 64 per cent of the population was hopeful about the future, while in 2016 it was 75 per cent. In October of 2023, Ipsos found that 60 per cent of Canadians have given up on owning a home. With Millennials the largest voting bloc in the country, they surely drive that number. Fight Club may not be relevant in its nihilism and search for recognition, but it sure hits home in its hopelessness. With the population booming, including in Alberta, this will only get worse before it gets better; despite our province still being cheaper in relation to others, our big cities are facing these pressures, too.

The novel also deals with the hyper-consumerism and capitalism that had defined the 1980s (think Wolf of Wall Street), showing multiple times that you need to let go of stuff to find meaning:

“I’m breaking my attachment to physical power and possessions,” Tyler whispered, “because only through destroying myself can I discover the great power of my spirit.”

Thankfully, Millennials’ disavowal of materialism (at least in theory) did not take the same track as the novel’s version did. History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes, and so too does generational culture.